Yonia Fain's Paintings of Suffering

An under-appreciated Holocaust artist's works of anguish and pain which resonate today

Recently I have been re-visiting work of the late artist Yonia Fain, who lived a full life, dying at age 100 in 2013, but never achieved the name recognition or acclaim he deserved.

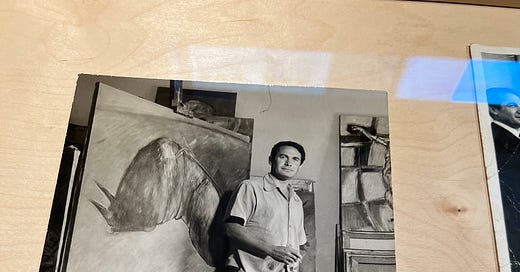

Photo of Yonia Fain with his painting of a slain bull, Untitled (1954-1955)

Fain was born in what is now Ukraine in 1913, then fled to Vilnius, Poland with his family as a child. When Nazis invaded Poland in 1939 he was living with his first wife in Warsaw. They escaped by foot to Russia, where he was conscripted into the Russian army as an artist. He refused to create propaganda art and so he was in danger. He falsified documents and a visa which was signed by the famous Japanese diplomat Chiune Sugihara, and escaped through Siberia into Japan, living in the Shanghai ghetto and becoming part of a third wave of Jewish refugees in Shanghai in the fall of 1941. In Japanese-controlled Shanghai he made a living by painting portraits of Japanese officers and their families. In Shanghai he wrote poetry and had exhibitions of his paintings. While he and his wife escaped Europe, no one else from his family did. From 1947 to 1953 he lived in Mexico City (where he and his wife divorced) and taught at the University of Mexico; he became close friends with muralist Diego Riviera. In 1953 he moved with his second wife to New York City, which was the center of the art world after World War II, where he exhibited in city galleries and taught at the Brooklyn Museum, then NYU, and then Hofstra from 1971 to 1985, when he retired. He was named faculty emeritus by Hofstra in 2013.

In New York City after WWII, Abstract Expressionism was at its height, but Fain didn’t want to conform. Karen Albert, director of the Hofstra University Museum of Art, said in a April 29, 2021 lecture “Yonia Fain: Witness to History,” “Yonia didn’t fit into any of those categories [of Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism or Pop Art] as an artist. It gets harder for an artist to fit into the gallery system when he is not working in the most popular manner. He didn’t want to give up representation [in his art]. He really felt he was a witness to what had happened in his life and he didn’t want people to forget. The idea of not forgetting and remembering was very important to him. He said it all the time.” Fain’s refusal to conform to the popular style of art, his commitment to representative or figural art as the best way to be a witness to history, despite it being opposed to the popular style, prevented him from becoming well-known. Still, he kept painting and teaching, which Albert says, he enjoyed very much.

I actually saw Fain’s work for the first time three days after October 7, 2023, when I went to see an exhibition of his work at the James Gallery at the Graduate Center, CUNY, “Modern-ish: Yonia Fain and the Art History of Yiddishland.” Many of the works were from the permanent collection of Hofstra University Museum of Art, which owns 122 of Fain’s works. His work spoke to me then, not fully aware of the horrors of October 7 as accounts were still dribbling in. I was in a state of shock at the knowledge that Hamas terrorists had invaded kibbutzes and the Nova Music Fair and murdered many Israelis, though I didn’t yet know the full account, the rapes, the burnings, and glee with which Hamas committed their brutality, nor how protests would erupt on American campuses against Israel and for Hamas, and hostage posters would be torn down.

Prisoners (1970s), photo by Laura Hodes

His paintings are incredibly emotionally expressive. Several of the paintings spoke to me in their portraits of anguish and suffering. In Prisoners (1970s) five figures seem to be possibly hanging, their garments suspended in space. They are lifeless and have lost control of their fate, their figures lined up in a row. Some think the uniforms are hanging without bodies, as Albert puts it, “representing people dead and missing from his life, the empty uniform a recurring motif.” I see the ghoulish facial features in one figure, though, suggesting the presence of bodies. The pastel blues and greens contrast with the suffering presented, suggesting the indifference of others to the prisoners’ pain. I don’t think I knew then about the hostages, but the inhumanity of how men could seize life and freedom away from other men spoke to me.

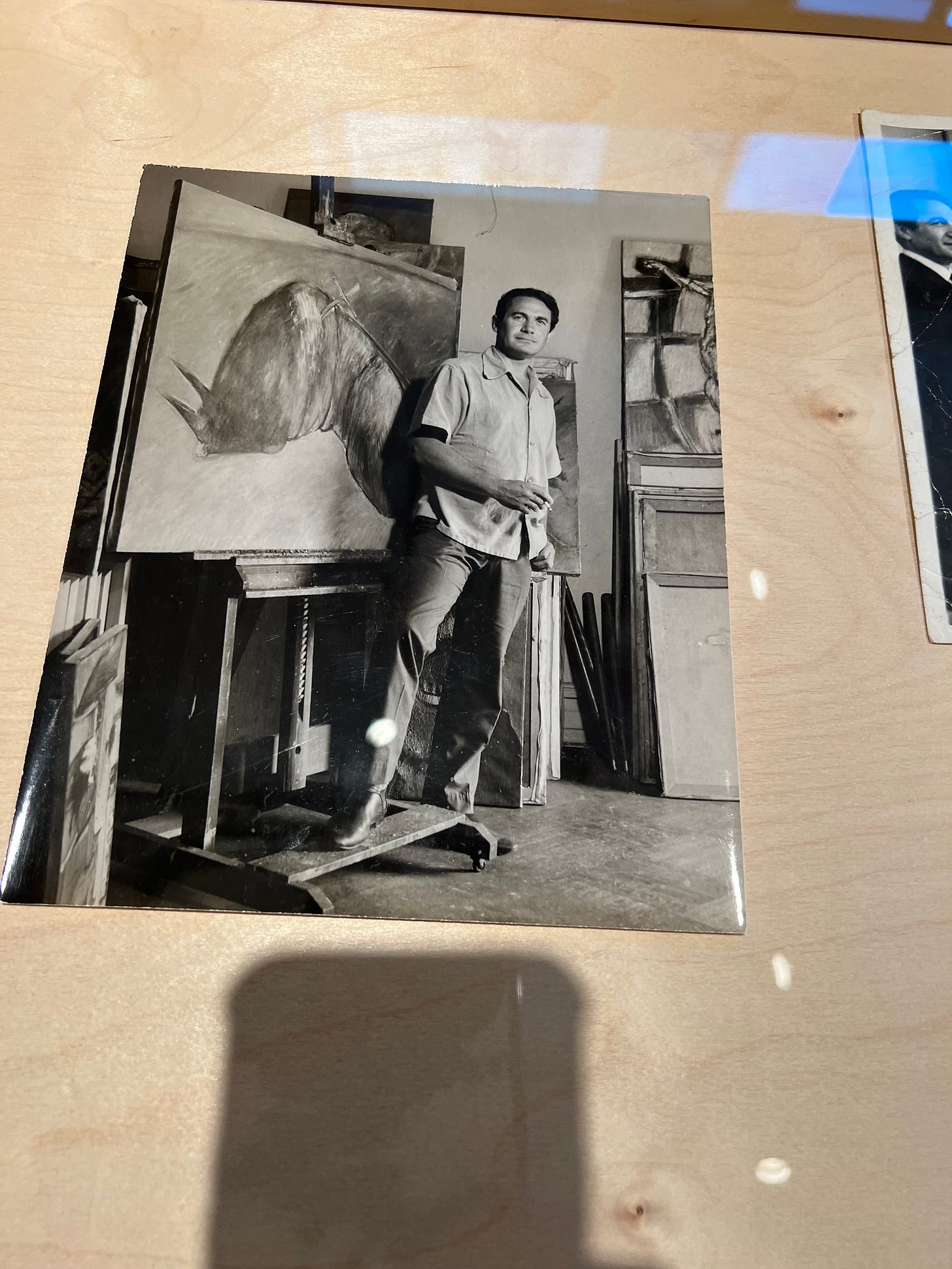

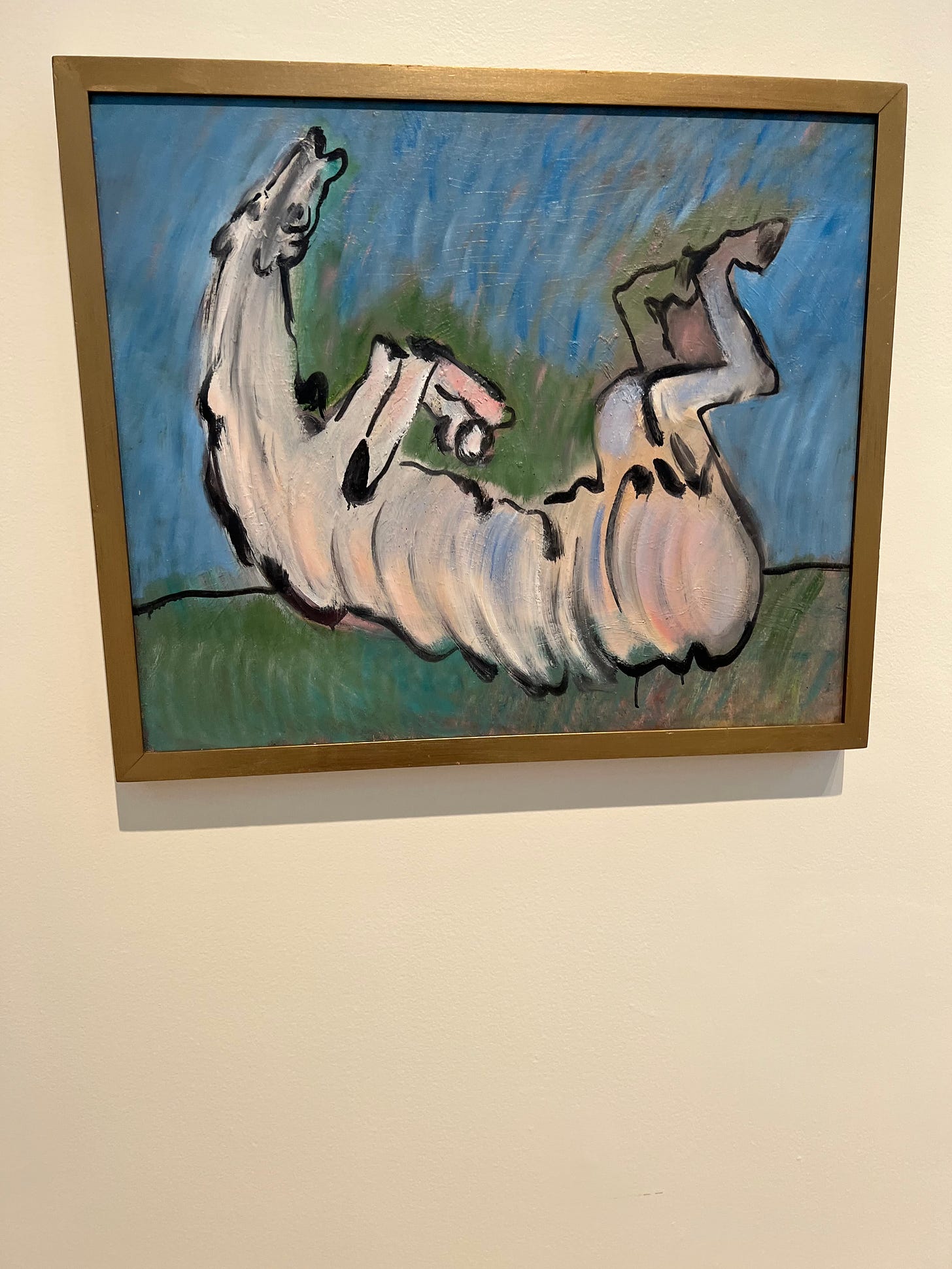

Crucifixion (1966)

Similarly, there was a Crucifixion painting (1966), Fain one of several mid-century Jewish figurative painters, including Chagall and Abraham Rattner, who painted the Crucifixion not as a religious expression, but to convey man’s inhumanity to other men, and to stir the empathy of viewers towards the suffering of another person different from themselves.

Holocaust (no date), photo by Laura Hodes

Fain’s large painting, Holocaust (no date), the largest in the exhibition, is more abstract than his others; one can make out the image of an anguished horse in the center, and on the lower right, a pair of human arms clutching at each other, evoking the hands in Picasso’s Guernica, and in the upper left, scythes or blades, a repeating motif of his – but the overall impression is a maelstrom of upheaval and pain.

Storm (no date), photo by Laura Hodes

Similarly, Storm (no date) shows an atmospheric storm of wind and blood overtaking a town or shtetl, threatening to wipe it out. To me the painting evoked a foreboding sense of looking down at the kibbutzes on the eve before they were invaded. I stood before it and could feel the sweep of terrorists’ storming the peaceful kibbutzes, burning homes, blood staining the walls.

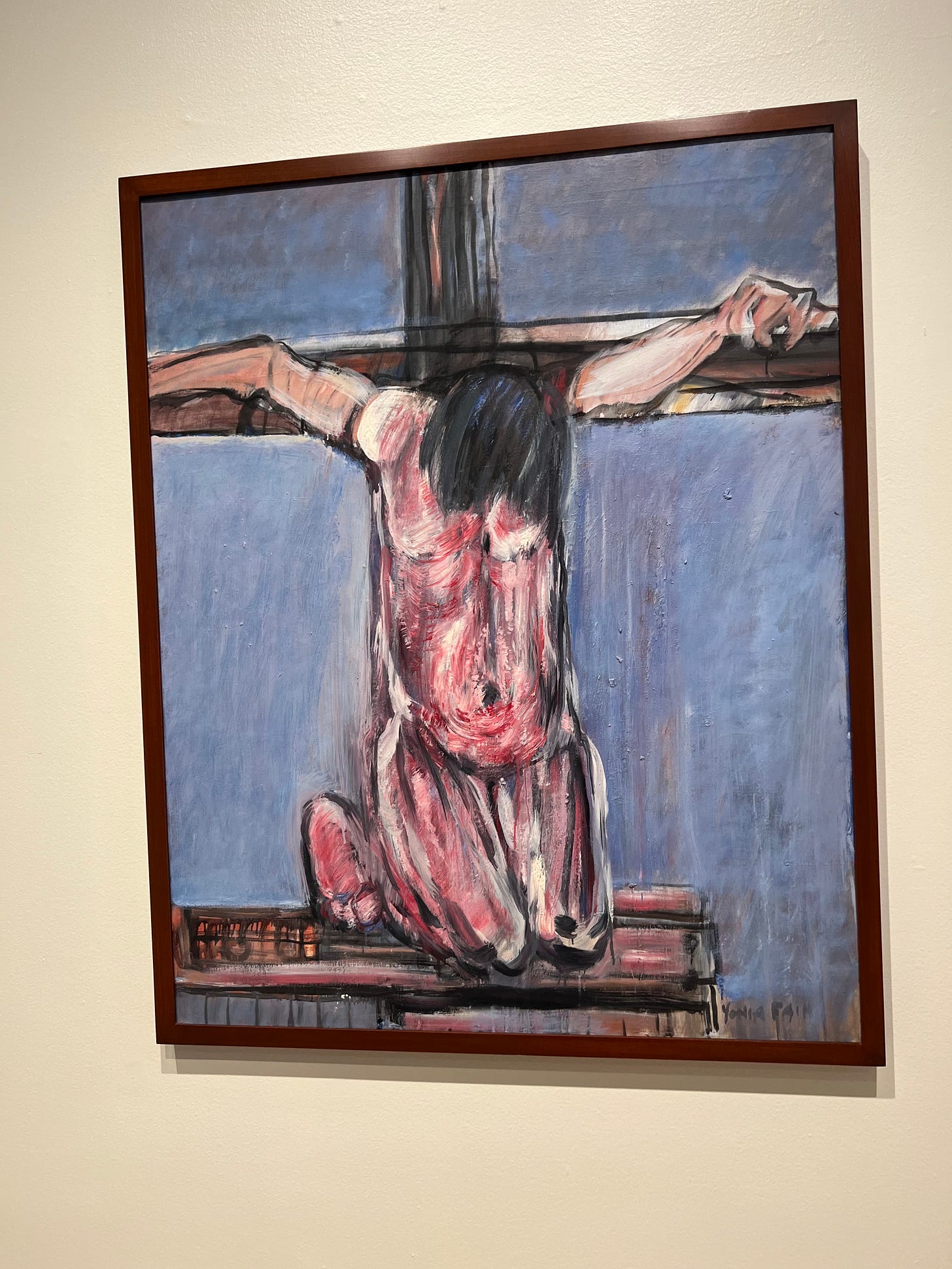

Two of his paintings evoke pure horror – Untitled (Dying Horse) (no date), a horse in state of anguish, wailing, and The Scream (1997), a distorted face of a man with an open maw making a similar wail of suffering and pain.

Untitled (Dying Horse) (no date) photo by Laura Hodes

The Scream (1997), photo by Laura Hodes

Interestingly, Karen Albert, who knew Fain for many years when he was at Hofstra, spoke in a 2021 lecture about how visiting his studio, with walls stacked with his paintings of grief and anguish, was overwhelming because of the depth of emotion emanating from the works. “But to talk to Yonia himself,” says Albert, “he was a kind and very gentle person. He couldn’t have been warmer and more welcoming. The difference between the person I knew and the images he painted was very dramatic.”

Fain was also a prolific Yiddish poet, authoring five books of poetry, and for a time he was President of the Yiddish Pen Society--and several poems were displayed in the exhibit. One seemed to speak about his personal mission, his internal drive that kept him painting daily until his death at 100. Here is an excerpt of one poem:

Paint the Day at Night (translated by Sheva Zucker)

Paint the day

By night

And the night

By day,

A picture

Is the landscape

Of thought,

A corner,

Where old age

Has spent

Its youth,

A burned down door

To a longing

Opened once more.

Don’t paint what you see,

Paint what you can not

Forget. . . .

Make the unknown

Known,

Paint fogs –

Letters from the mountain to the valley,

Paint,

The voice of silences,

And their echo,

Paint the intelligence

That makes the paintbrush

Serve

Your hand.

These words speak of Fain’s drive to “paint what you cannot forget,” to paint his experience of the Holocaust and of being a refugee in order to “make the unknown known,” to make people that have not experienced these horrors aware of them, so that others would not forget, to “paint the intelligence that makes the paintbrush serve your hand.”

In 2012, Fain began to experience macular degeneration, yet he continued to create drawings on paper every single day even as he lost his vision. To continue to paint is a hopeful act, one of resilience and survival. As the words of this poem suggest, Fain knew he was a servant to his paintbrush, to the imperative to paint what he could not forget so that he could make others remember.